What parents should know about cleft lip or palate

November 21, 2025

Categories: Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery, Pediatrics

Tags: cleft lip, Cleft Palate

When parents hear cleft lip or cleft palate, it can feel overwhelming. These are among the most common birth defects, but they come with questions. What exactly is a cleft lip or palate? How are they treated? And what does life look like for a child born with one? The answers start with understanding how these conditions develop and what care looks like.

What is a cleft lip and palate?

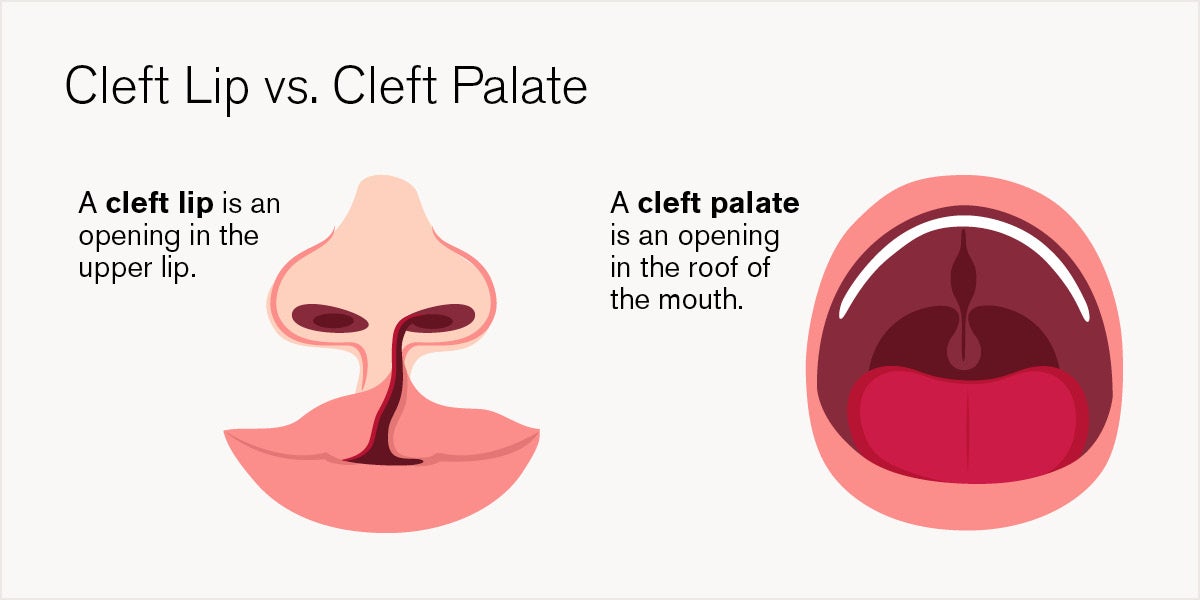

A cleft lip and cleft palate are related but distinct conditions. The difference comes down to location and the structures involved.

- Cleft lip is a separation in the upper lip. In severe cases, it can extend into the nose.

- Cleft palate is an opening in the roof of the mouth. It can also involve the soft palate, hard palate and even the tooth-bearing area of the upper jaw, known as the alveolus.

Each can have different effects on the development of a child. For example, a cleft palate often affects speech and swallowing and has a higher chance of being linked to other hereditary conditions. In fact, about 30% of cleft cases are associated with genetic syndromes.

“The most severe deformity is to have a complete cleft lip and palate. And if it’s bilateral, meaning on both sides, then that’s obviously more severe,” says Steven Daws, MD, DMD, pediatric craniofacial surgeon at Loyola Medicine. “But some people just have an isolated cleft lip and some people have an isolated cleft palate.”

What causes cleft lip and cleft palate?

Cleft lip and palate develop early in pregnancy, usually between weeks 4 and 10, when the tissues of the lip and palate should fuse together. When they don’t, a cleft forms. Most cases are multifactorial, meaning they result from a mix of genetic and environmental factors. While the exact causes are unknown, the risk of a cleft can increase with:

- Maternal smoking during pregnancy

- Folate deficiency

- Diabetes before pregnancy

- Certain medications, such as some used for epilepsy

Other factors include poor maternal health, alcohol use and nutritional deficiencies. Still, many cases occur without a clear cause, and most families have no prior history of clefts.

How is cleft lip and palate diagnosed?

Cleft lip is often detected during a routine prenatal ultrasound, sometimes as early as 13 weeks. Cleft palate is harder to see and may not be diagnosed until birth or even later if it’s a submucous cleft, where the surface looks normal but the muscles underneath aren’t positioned correctly. These cases often come to light when a child struggles with speech and a therapist notices something isn’t moving as it should.

“Doctors can see a cleft lip on an ultrasound, but that’s not always the case for cleft palate. It’s not unusual for parents to be surprised by a cleft palate that was not previously detected,” says Dr. Daws.

Craniofacial surgeries for cleft lip and palate repair

While a cleft lip and palate can be concerning for both parent and child, treatment is highly standardized and involves a team of specialists. Here’s what the typical timeline looks like:

- Cleft lip repair (cheiloplasty): This surgery closes the gap in a baby’s upper lip and is usually done around 3 to 6 months of age. This timing allows for anesthesia safety and gives time for pre-surgical molding, which helps bring the segments closer together for a better repair.

- Cleft palate repair (palatoplasty): This surgery closes the opening in the roof of a child’s mouth and is typically done between 10 and 18 months, before a child starts forming words to prevent speech issues.

Secondary or revision surgeries:

After initial cleft lip or cleft palate repair, several follow-up surgeries may be needed to support function, appearance and development as the child grows.

The child may need lip and nose revision surgery to reshape the nostrils or smooth lip scars. Between 3 to 6 years old, speech surgery closes the gap between the soft palate and throat to assist in speech development.

Around ages 7 to 9, an alveolar bone graft fills the front part of the jaw so permanent teeth can erupt properly. Later, many children need jaw surgery to correct underbite and rhinoplasty to improve breathing and appearance.

On average, children undergo 8 to 9 surgeries before adulthood.

Speech therapy is almost always part of care, even after surgery. Most children need some level of therapy to correct articulation and compensate for structural differences.

“Almost every child who has undergone surgery for a cleft lip or palate gets some amount of speech therapy,” says Dr. Daws. “Thankfully, it’s not usually overly burdensome for families because many children receive therapy through school programs.”

Feeding and early care tips for children with cleft lip or palate

Feeding can be challenging, especially before surgery, but there are solutions. Babies with only a cleft lip usually feed well after learning to latch. Those with a cleft palate may need special techniques or use specialized bottles and nipples which help control flow and reduce air swallowing. A few things to keep in mind are:

- Hold the baby upright during feeding to prevent milk from leaking into the nose.

- Expect more frequent burping, since babies with cleft palate often swallow extra air.

- Regular weight checks are important to ensure proper growth.

Despite these challenges, most babies gain weight normally and thrive with proper support.

Loyola Medicine provides compassionate care for every child

Fortunately, today’s care for cleft lip and palate is more advanced and compassionate than ever before. At Loyola Medicine, families are never alone in this journey. Our multidisciplinary team, made up of expert surgeons, audiologists, speech pathologists, geneticists, psychologists and more, works together to provide personalized, comprehensive care from infancy through adolescence. With cutting-edge surgical techniques and a deep commitment to whole-person healing, we help children not only overcome the challenges of cleft conditions but thrive beyond them.