Living with Bell’s Palsy and Facial Nerve Weakness: What Are My Options?

August 11, 2025

Categories: ENT/Otolaryngology

By Amy Pittman, MD, Otolaryngology, Facial Plastic Surgery

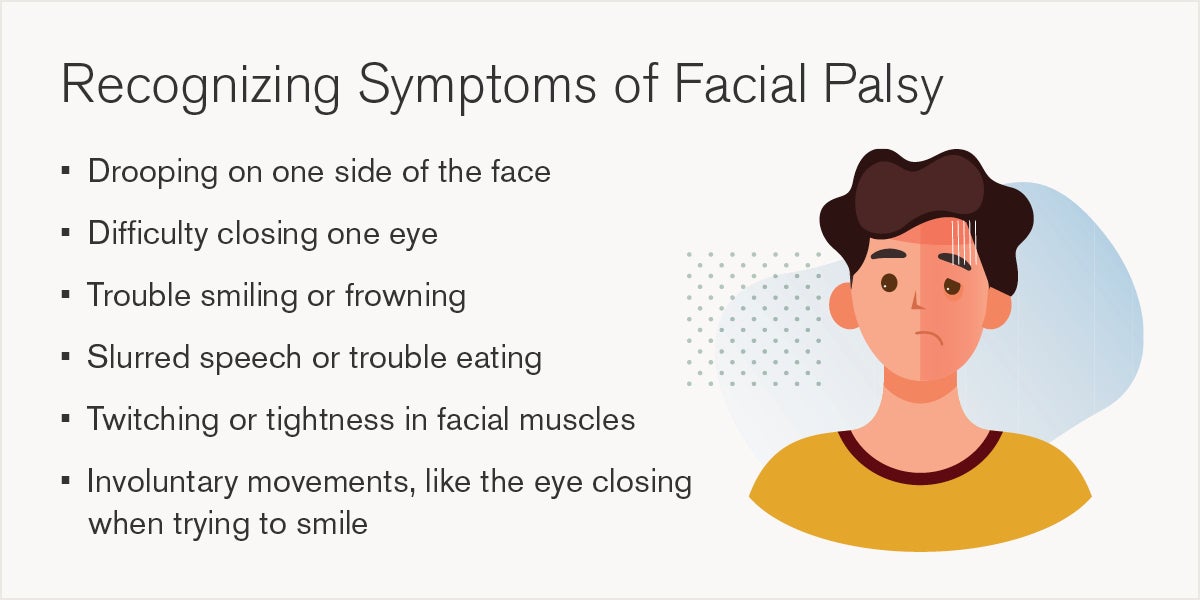

Facial nerve weakness, known also as facial palsy, can be a sudden and overwhelming experience. It affects how we smile, speak, blink, and express ourselves. For many, it’s not just a physical issue, but can also impact confidence, communication, and quality of life. Whether caused by Bell’s palsy, trauma, or another condition, understanding your options is the first step toward recovery.

Facial nerve weakness, known also as facial palsy, can be a sudden and overwhelming experience. It affects how we smile, speak, blink, and express ourselves. For many, it’s not just a physical issue, but can also impact confidence, communication, and quality of life. Whether caused by Bell’s palsy, trauma, or another condition, understanding your options is the first step toward recovery.

“Facial palsy is such a devastating diagnosis in the beginning because it’s such a drastic change,” says Amy Pittman, MD, an otolaryngologist and facial plastic surgeon at Loyola Medicine. “But if the body can’t heal the process on its own, there are many tools we can use to help get things going.”

What is facial nerve weakness?

Facial nerve weakness (facial nerve palsy) happens when the seventh cranial nerve, called the facial nerve, is damaged or inflamed. This nerve controls the muscles that allow us to show emotion, close our eyes, raise our eyebrows, and move our lips. When it’s not working properly, these muscles may become weak or even paralyzed.

The weakness can range from mild to complete paralysis. In some cases, people can still move parts of their face, while others may lose all movement on one side. Bell’s palsy is the most common cause and often appears suddenly, sometimes overnight, resulting in weakness or paralysis on one side of the face. Other causes include head injuries, tumors, infections, or complications from surgery.

“Facial weakness is essentially equivalent to paralysis,” Dr. Pittman says. “Bell’s palsy is just one of the most common causes. It’s a viral condition that can cause the entire face to stop working over the course of a few hours.”

How is facial nerve weakness diagnosed?

Doctors typically diagnose facial nerve weakness conditions, such as Bell’s palsy, through a physical exam and a detailed medical history. They look at how the face moves and ask how and when symptoms started. In some cases, imaging tests like CT scans or MRIs may be used, especially if trauma or a tumor is suspected.

“The best tool we have is a good physical exam,” says Dr. Pittman. “We also use grading systems to qualify the degree of weakness, but the patient’s story is really critical to understanding what’s going on.”

Treatment options for facial nerve palsy

Treatment depends on several factors, including the cause of the weakness, length of time, and severity. It is imperative to seek medical care as soon as possible for an accurate diagnosis and to initiate immediate treatment.

Early stage (first few weeks)

If the weakness is caused by Bell’s palsy, doctors often prescribe corticosteroids like prednisone. These medications reduce inflammation and improve the chances of full recovery, especially if started within the first 72 hours.

Eye care is also critical. If the eye can’t close properly, it becomes vulnerable to dryness, irritation, and even damage. Patients may need to use lubricating eye drops, ointments, or wear an eye patch to protect the eye.

In this early stage, the focus is often on monitoring and supporting the body’s natural healing process.

Intermediate stage (6 months to 1.5 years)

If facial movement hasn’t returned after several months, doctors may consider more advanced treatments. One option is a nerve transfer. This involves rerouting a healthy nerve, often the masseteric nerve which helps with chewing, to stimulate the facial nerve. This procedure “jumpstarts” movement in the facial muscles.

Nerve transfers are most effective when done within 6 to 18 months after the injury. After that, the facial muscles may begin to atrophy (shrink and weaken), making recovery more difficult.

Late stage (beyond 1.5 to 2 years)

If the facial muscles have been inactive for too long, they may no longer respond to nerve signals. In these cases, doctors may recommend a muscle transfer. This involves taking a muscle from another part of the body, often the thigh or lower leg, and transplanting it into the face to restore movement.

“If a facial muscle hasn’t moved for three years, it’s never going to work again,” says Dr. Pittman. “That’s when we consider muscle transfers to actually replace the facial muscles.”

While more complex, muscle transfers can significantly improve facial symmetry and function for patients with long-term paralysis.

Supportive and ongoing treatments for facial drooping

If you have a condition like Bell’s palsy, your face may not be smooth or symmetrical, even if some movement returns. That’s where supportive treatments come in:

- Botox therapy: Botox is often used to treat synkinesis, unwanted movements caused by misdirected nerve regrowth. It can also help balance facial movement by relaxing overactive muscles or reducing distracting motion on the unaffected side.

- Physical therapy: Specialized facial nerve therapists guide patients through exercises that improve muscle control and coordination. Loyola Medicine is the only hospital in Illinois to offer this level of facial nerve physical therapy.

- Selective neurectomy: This newer surgical option involves cutting specific nerve branches to reduce unwanted muscle activity and improve facial balance.

Loyola’s multidisciplinary approach to facial nerve disorders

Loyola Medicine’s facial nerve disorders program brings together a highly experienced team of experts to create personalized treatment plans for patients experiencing facial nerve weakness or paralysis, such as Bell’s palsy. Patients may meet with:

- Neurologists who help diagnose and manage underlying causes

- Facial plastic surgeons who perform nerve and muscle procedures

- Ophthalmologists who protect and treat the eyes

- Physical therapists who specialize in facial rehabilitation

- Psychologists and counselors who support emotional well-being

Facial nerve weakness can feel isolating and overwhelming, particularly in the early days. But many people recover fully, especially those with Bell’s palsy. And for those who don’t, there are more treatment options today than ever before.

“There’s always something we can try to make things better,” says Dr. Pittman. “If it’s not happening on its own, we know what to do and when to do it.”

Amy Pittman, MD, is a board-certified otolaryngologist and facial plastic surgeon at Loyola Medicine. She specializes in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of facial nerve disorders, including facial paralysis and synkinesis. As an associate professor and key member of Loyola’s multidisciplinary facial nerve disease program, Dr. Pittman brings extensive experience in advanced procedures such as nerve transfers, muscle transfers, and Botox therapy for facial reanimation.